For Steve Solinsky, part of the namesake of the Mowen Solinsky Gallery, retirement does not mean kicking back and doing nothing. Steve talks with Kathy Frey about how his spiritual life has blossomed and how that has increased his awareness around photography, which he still very much enjoys when time allows.

KF: What’s been going on in your life and studio lately?

SS: This is interesting because in the last couple of years being “in retirement,” but really still being busy, what I’ve been doing has been more developing my meditation practice, my spiritual self. Part of that – I’ve had a long, ongoing project of something I’ve been wanting to do — is to put together a book of images.

For a long time it’s been a question of having the images yet wondering what the book is going to be. What’s going to bring them together? That’s the key. If I look around and see what other books of photography are, a lot of times people will do a subject or a place.

In reflecting on my work – I’ve done a lot of reflecting – it’s like ok, I love my photography and it’s really intuitive for me, but what the heck does it all mean? What am I doing?

I’m putting a lot of energy in that direction with asking myself those questions because that’s what I want the book to be. I want the book to be about what I do and what happens. What the process is.

As it turns out, it ties in really well with my spiritual practice. And so what I’ve seen is a parallel between the two – my photography and my spiritual practice — so that is how I’m going to approach it, by weaving in the photography and what I would call “the art of seeing” with development of a spiritual self.

It’s a process of awakening, even though I use that word with some trepidation because I think it’s misused a lot and not really well understood. But it’s definitely in the process of how I see myself right now, awakening.

I see photography as being very similar. It’s a process of awakening to the senses. Mostly your visual sense. Developing that art of seeing. Which is something we’re not taught anywhere… how to see. It’s something intuitively I figured out along the way was happening with me.

KF: Did you see your images change over time with that evolution in your awareness of your process, ways of seeing, and process of awakening?

SS: Yes. I know that in the beginning I was excited by photography because I’d seen wonderful examples of other photographers that did really exciting work. There were several of them. Probably the earliest examples were what I saw through Sierra Club imagery, so they were definitely nature oriented.

I think what happens when you experience an example of something that is done well, it leaves an imprint on you. You get an idea of “oh, okay, this is about nature and capturing nature.” When I experienced those images I had great feelings and got very excited. What I found was I would go out photographing and invariably I would duplicate to some degree some things that I’d already seen… like a particular subject.

An example might be neophyte photographers that go out to photograph an old barn because an image of an old barn had resonated with them before… that was a nice image, I really like that… you want to do it. A big part of doing something is the mind telling you this is how you do it, this is how you approach it. You go out and start looking around for things… in this case, keep your eye out for old, cool barns.

That sort of approach invariably happened, and what I discovered after a few years was that the photographs I was taking started losing their excitement for me. They began to feel a little more dull as I went on.

KF: Do you think that was due to authenticity?

SS: No, I think what excited me in the beginning, first of all, was the novelty, not having seen anything like these photographs before, and it was also the experience – the feelings – that arose in me in seeing the images come to reality.

The aesthetic response that I was feeling was more a whole body experience and it didn’t really have anything to do with the mind. I think when the mind looks at an image, the mind is grabbing on to the sorts of things that the mind grabs.

That’s the problem we’re up against when we’re really trying to see, we start looking. As soon as we start looking for something, then we’ve missed the mark.

KF: How do you keep it fresh… keep yourself from looking?

SS: I noticed that the photographs that I took that were successful, that remained exciting for me, I never got tired of looking at them. I still look at them and go: wow, that’s great… there’s something about that I really like. And I don’t get tired of it.

So, I started intuitively asking questions: what is that about?

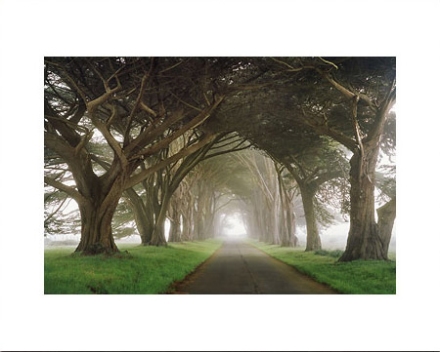

The best I could come up with is, invariably, these subjects that I photograph come out of times when I’m definitely excited, I’m really present to what’s happening, and I’m really looking at the light. It’s the light. It’s finding that amazing light on things.

After a while of pondering this over and over again, saying “it’s the light” is just another way of saying “it’s in the moment.” It has to do with the quality of things and not what they are.

So, therefore, going out looking for something is not going to bring you to what you’re trying to find. The only way to approach it is to be awake and to really pay attention to the light.

KF: And to capture what’s there, it sounds like.

SS: Right, and to also pay close attention to how you’re feeling. Your response to looking at things. Because ultimately that’s the key. It’s like trying to find uranium. You have a Geiger counter and when it gets close, it starts chattering. It’s the same thing. The eyes are connected someplace deep, to something inside us that recognizes and will respond in a feeling way to things.

When I look at the photographs that really send me… that’s what happens inside me, that chattering. So, when I’m out in the field, it’s like I’m going through a pile of photographs… the moment that shows up and makes me go “oooooh,” that’s the experience I’m looking for when I’m out in the field.

KF: How do you capture and compose images?

SS: It’s a process of using the camera. Early on I was using a view camera. I didn’t have a camera I could just look through, so I used a white cardboard cutout in the format of the view camera screen.

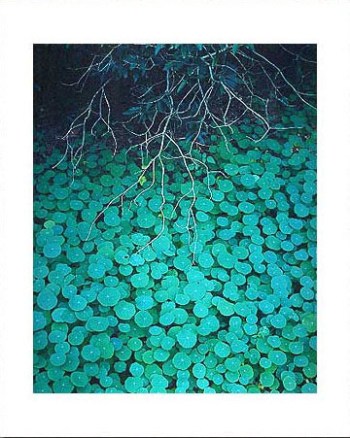

Something would attract my attention – whether it had to do with the light or the forms. It’s really difficult to define what it is because it’s mysterious… but there’s a recognition that happens. It has to do with the forms, the color, the quality of the tones and the light, and it also probably has to do with what it is – what it is may come into play in some symbolic, deep way that’s not obvious. I would hold the white frame up in front of me to help identify that trigger.

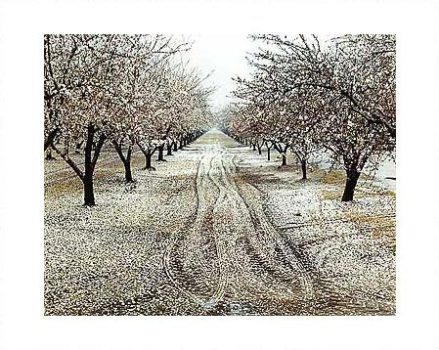

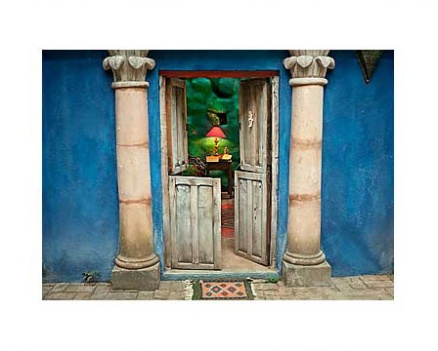

Usually I would do most of my photography on trips, where I’m in a new place, although it doesn’t have to be that way. I just tend to get more excited when I’m in a new place and there are new forms and new colors. I’m not sure what I’m going to find. I don’t know where I’m going. That sets it up for accidents to happen.

And even if I do sort of know the territory – I’m not in a foreign country or something – often what I’ll end up doing is I’ll drive or walk, and in driving, I’ll just drive. A lot of times I won’t even know where I’m going. I haven’t any particular destination in mind, but I’m just looking to see what I see, to see what I find and to see what captures my attention.

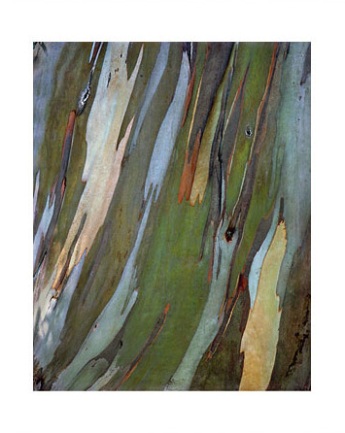

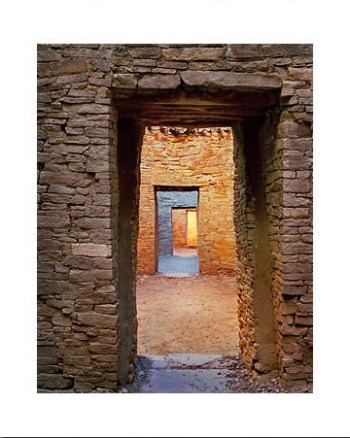

In analyzing the really successful images, I came to a conclusion that there are three components that are happening: one is that there’s some physical subject with some kind of form, and you end up positioning yourself so the form changes a little.

There has to be some kind of light falling on it. Now the light is very important and is changing all the time throughout the day. You can have the same subject at different times of day and different conditions, and it’ll have a completely different feeling depending on the light. That was another lesson to me… again, it has to do with accidents and what happens.

The third component is you have to be awake. You have to be paying attention and noticing when you have a response to something. Those three things are always happening in a successful photograph.

KF: Do you ever try to force those? Like if you see something and the light isn’t perfect, do you return back?

SS: Sure, to an extent. Recently I was going down to the city [San Francisco]. It’s been quite a few years since I’ve photographed Fort Point, so on this one trip I thought huh, that would be fun. Why don’t I just stop there, go through it, and see what I can find.

So, there, I did pick a particular location, although I still didn’t know exactly what I would find. And, of course, it had changed since years ago when I’d been there. The spaces had changed. They weren’t the same, so it was a different opportunity.

One of the Buddhist tenets is impermanence. In doing photography, when you live in a place and you move around and you have a chance to see things over time, you really see that things are changing, always, all the time.

There are photographs that I’ve taken, real popular ones, that I’ve gone back to the location just to say “hi,” just to sort of check in with the subject – so many times, invariably, it’s different. Definitely the light is different, but, beyond that, the subject has changed. Something has shifted, something’s moved, something’s grown so you can’t see what you saw before. So it’s always changing. It really reinforces that idea of accident and being in the moment and just being awake.

And that’s, of course, my practice too.

KF: In thinking about a book, I look at your images and see that some are travel, some are still lives, some feel like very special places.

SS: Yes, well remember, that’s thinking about them as subject. They can be anything. It’s just something that has attracted my fascination.

KF: Do you imagine the book to be more about that? More meditations in a sense?

SS: Yes. I did a workshop on creating photographic books with a mentor of mine, and the first title I came up with was “Nowhere in Particular.” Depending on how you did the type, “Nowhere” could be “Now Here.” I thought that’s cool, I like that, and that sort of says it: what we’re photographing is nothing in particular and nowhere in particular.

KF: And now here, in particular!

SS: Right, right! That’s what it is.

I’ve gone on, and now my idea is more about directly bringing in the process of awakening and seeing. So I’ve got some titles that relate more to that and intersect the two.

It gets back to the idea of accidents, and how I really believe there are no accidents. There are synchronicities at work.

If you have the intention – here we get back to the Buddhist principles – intention is extremely important in anything, especially in a spiritual practice, and true in photography too — my intention, at some point when I got serious, was “I think I’m really going to go for it. I really want to wake up.”

KF: When was that? Recently?

SS: That was a couple of years ago. I got serious in Qi Gong practice, which I think has really brought a new dimension to meditation and that side of the practice. Qi Gong is real body oriented, and it brings in the breath.

That has all come together for me in a blossoming of my Buddhist practice. With some trepidation, I would call it a process of awakening. I’m not talking about enlightenment. Enlightenment is maybe on the path, but it’s on the path… the question is, are you on the path? You’re not going to get to enlightenment unless you’re on the path. The path is the path of awakening.

What I see in the process of awakening, I can see in the photography. That’s sort of an element of it. Just awakening to your senses and what you’re feeling.

KF: What are some of your other interests?

SS: I have real interest in my Buddhist practice – spirituality — and science. So I started seeking out sources like that on the Internet… people who were interviewed, scientists or whoever had something to say about what consciousness is… like quantum physics.

I feel so excited about living in a time when scientists say that the universe is conscious. In fact, just your experiencing something, your perceiving it, is forming it, creating it. In other words, it’s changing it. It has an effect.

What there is, is what we perceive, which is energy. It’s an interaction of energy, and we are energy. It all gets wrapped into consciousness. The whole enchilada is conscious.

If there is a material world, whatever we call it, at this point it really looks like there is no material world.

KF: Has consciousness been there for you all along, or has it come up once you moved beyond those monetary and work demands into retirement and made room for it?

SS: There are different worlds we live in, different paradigms. There’s a problem in dwelling only within one paradigm, especially the material paradigm. That’s just the way it is. I didn’t design the world. Even though you could say there is no material world, the fact of the matter is, certainly a whole dimension of our being is one inhabiting a material world.

We do need bodies to inhabit this world. We’re getting real basic here, but I would say that the reason there is a material world, the reason we’re alive, the reason we’re here is so we can work in some way on our spiritual selves, in some way evolving and perfecting that. Part of that happens in a material dimension, even though we might say it’s not real. What we think and what we do in this material realm make a difference.

It’s a paradox.

KF: I like that idea that we cohabit different worlds and give them different priorities. Some people make extreme choices to create their own worlds, like nuns or monks, but most of us work and live in a general society.

SS: Part of that awakening, that opening up process, has been a movement from identification with separation and action — doing things — to moving into more a sense of connection and singularity with all things. A real evolution, development of compassion and a sense of caring and love for other people and other things – nature, you name it — recognizing or somehow seeing or feeling a deep connection with all things, that makes a difference.

If you feel that way, then maybe your instinctual reaction to things is not to be competitive and to think in terms of things as “it’s either me or them,” or “I’ve got to take care of myself.” I think there’s an overflowing sense of abundance, and actually that creation — the universe, this world — is a friendly place. And there’s a lot of help out there, if you ask for it.

KF: And if you’re open to receiving it.

SS: Right, you have to be open to receiving it.

One of the things I’ve come up with is that to really welcome — to really engage that process of awakening in changing your world — you have to shift paradigms. In other words, your beliefs, your actions, and your feelings are all very important. When those shift, when all three of those things change, then your world is changed. And when that has happened, then anything is possible.

But to try and awaken from your old world using your old paradigm, ain’t gonna get you there, because part of your old paradigm says “you can’t get there from here.” Part of the old paradigm is a denial that it’s even possible.

KF: I know you’re involved with the meditation center here in Nevada City, yet I don’t know what your involvement is. Would you be willing to talk about that?

SS: Like a lot of people, I’ve been one of the members of the Mountain Stream meditation group and we’ve always been meeting in different places, but the last 10 or 15 years has been at Wild Mountain, a local yoga studio.

A donor stepped up for our group and offered the money for a facility. That made it a possibility, and that set things in motion. I was on the board of Mountain Stream and, because of my interest in architecture (the fact that I had a degree in architecture), I got really excited and interested in the possibilities. Because I had that experience in architecture, I would be a good one to look at properties, to see what the possibilities might be, what we might want to do and whether or not it might work.

I took that on, and I was excited to do it. The prospect of a real, physical center was exciting. I helped assess how we would get a meditation room out of the buildings we saw: is this building going to do everything we want? …all those questions. One thing lead to another, and we ended up finding a property on Zion Street and buying it.

Then I just continued the process… coming up with a real plan and working with an actual layout plan of the building. Because I had the skills to do it, I took it on, though I’m not an architect but at least I have that background, that experience. We were able to hire an architect in town to be the signer on things, and he backed me up as a consultant when there were things I wasn’t sure about.

With his input and with everybody getting involved at different stages, we came up with a plan.

KF: It’s an open, functioning center now, right?

SS: Yes, yes, it is.

KF: And is it open to the public or is it just for members? How does it serve the community?

SS: It’s definitely open to the public, although at this point our hours are set. It’s not open 24 hours a day. We have a program schedule with various sittings. It’s all online [http://www.mtstream.org/].

We did the interior, and the building is functional and works fine, although there are a few things we may do yet to make it better. Our long range idea is to try to make it more available for people just to stop in. We’re moving in that direction in a couple of ways.

We are currently looking for somebody that could be the person on site that is Mountain Stream… that can call the shots and basically be the managing director. We already have a board, and we have John Travis, our guiding teacher. The board listens with a special ear to what he has to say, but we do need a person on the site who can make decisions and maybe somebody that would be there that could open the building up at certain times or, if not, arrange volunteers to be there who could do it.

It looks like that’s the direction we’re going now. The center may be open at certain times during the day for people just to drop in.

Beyond that, our Phase 2 plan, is the back yard. The center has a really beautiful, big back yard. It’s one and a quarter acres. The idea we’re looking at right now is developing the back yard in a way that would be beautifully landscaped. It has old planting in it now. It used to have a swimming pool, and we took that out.

What we’d like to have back there is a meditation gazebo so that small groups, maybe 20 people, could actually sit inside of it with a teacher. The gazebo would also function as a stage for large outdoor groups where there would be chairs spread out in an arc on the lawn and the teacher would be on the raised gazebo.

If the building wasn’t open, somebody stopping by could go in the back and sit. There would be benches and places to contemplate. There’d be a labyrinth if somebody wanted to walk a labyrinth. They wouldn’t have to be indoors. That way people could drop in at any time.

KF: Despite retirement, this sounds like a full-time gig you’ve had with the meditation center. How do you feel about doing this work?

SS: With the meditation center, it’s been almost full time for the last couple of years. Certainly during the design process… a lot of my time was taken up doing that because we wanted to get the plans done. There was pressure to get things done, so I gave it my time for months and months.

In the last week I’ve been putting up the signs for the place to identify it. This is work that I just enjoy doing. I mean, nobody’s paying me for this. It’s just a beautiful center, and I want to see it become what it can be.

I’m doing everything I can to do that, and it just feels good. I think part of the awakening process — I mentioned that singularity thing and that natural compassion that arises — that’s part of it. You know that what you’re doing is going to be there a long time, and it’s definitely going to be a good thing. It’s going to help people.

KF: Did you get those types of feelings ever in your photography career as you sold pieces? Or, the inverse, were you worried about just putting more stuff in the world?

SS: It feels real clean to me. However, I will say, when I was doing art festivals and trying to sell more work, definitely that was when I was a little younger… there may have been more uncertainty and maybe more fear in there about “am I going to survive?” and definitely there was a competitive feeling because I could see somebody else doing well and selling well and that would make a difference… there are places I don’t tend to go right now because they’re not useful at all.

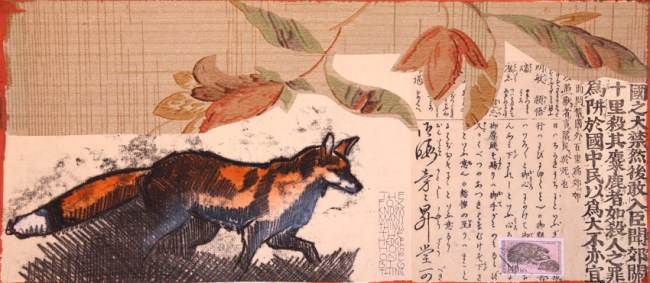

Doing the work was so rewarding, and the feelings that I had coming from it were so beautiful. If you take the premise that what you’re working with is beauty — beauty is probably the wrong word; I would say that they are objects or images of fascination — whether or not you want to equate that with beauty is up to you. But beauty, I would say, falls into the realm of the spiritual.

When people are responding to that, what they’re doing on some level is recognizing their own spirituality and their own connection to something greater… some amazing creative source that they’re reminded of and they go “ooooh! wow….” It’s all sort of unconscious.

That part came up more in taking the work out and showing it and then beginning to see that other people may have similar feelings to what I had. That has given me more to think about now.

I’ve thought a lot about art and what it’s about… like getting down to the question of “what is beauty?” It seems like they say “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” There are a lot of things they say about beauty that are interesting.

But is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Well, yes and no. There are certainly objects and things that many, many, many people would agree are beautiful, but not necessarily. So that’s an aspect I’ve looked at that’s going to be in the book somewhere.

But it’s that feeling of ooooh! It’s a wonderful feeling.

KF: Yeah, it’s ultimately that sense of connection.

SS: Yeah! So, providing people with little reminders of that… little places where they can connect with that aspect of themselves is a wonderful thing to spend time doing!

Getting lost in the marketplace and the worries of the marketplace is one of the pitfalls.

KF: Was that part of the initial desire of opening the gallery with John Mowen… to get out of that competitive art fair mentality, or was it from another place?

SS: No, you know, I think I wanted to be comfortable and not have to worry and think all the time about how am I going to make a living? Where is the money? I didn’t see myself doing shows forever.

So, if I’m not going to do shows, how’s it going to work? I hadn’t investigated that very much early on… I hadn’t found another way. So the initial thought was that having a gallery would be like an ongoing art festival. It’ll just keep providing.

Once we got into the project, and started opening and working on the gallery, the gallery became a work of art. Then it was another thing. Both John and I experienced that. It became obvious that it was not only ours but part of the community too.

We both owned it that way in some degree. We wanted to make something beautiful, a wonderful experience for people, and hopefully it would also make us a living.

KF: I won’t ask about that part.

SS: Yes, that part’s not easy. But the gallery is something I feel very proud about. Of course it’s ever changing. John is continuing on with it, yet it’s something I feel very proud of, and it feels like a service.

KF: When did you officially bow out of the gallery as an owner?

SS: I think it was about 4 years ago. Certainly after my stroke.

KF: And when was that?

SS: That was late 2007. Going on 2008. So, actually, it’s been 4 or 5 years.

KF: I know you’ve gone traveling since then as well since we have some newer images in the gallery. Do you have any sense of whether photography is still alive for you as far as taking photographs?

SS: Oh, it is! It definitely is. I can respond to that.

The intention and my heart are still very much into photography. How that manifests — whether or not I’m actually out photographing — is in my imagination and touching the feelings I have about it. It’s still extremely exciting to me!

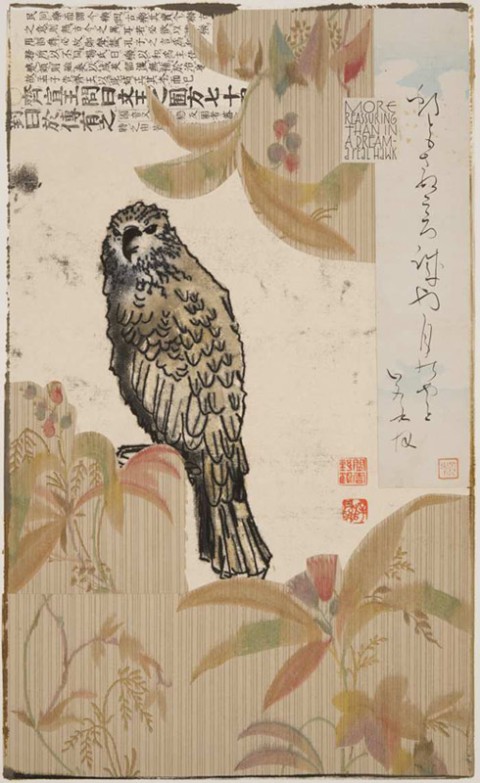

I see it as a source of wonderful feelings. I’ve had some really remarkable dreams about photography. One particular one – I’m sure I’ve had more than one – I’ll be photographing, and it’s the light! Wherever I am, whatever landscape I’m in… that light is happening.

I’ve got my camera, I’m photographing, and I’m totally in that feeling of… I’m totally transported. It’s hard to describe the feeling. It’s exciting, amazing,… there was a period there when right after college I was taking psychedelics, and actually I think my photography might be in some ways an attempt to touch that. Because that’s what it was. That was the experience of… I don’t know. How do you express that experience?

There’s something magical that happens. Anyway, those dreams… the power of the dream was seeing that light and the feeling it evoked. It’s a religious feeling.

KF: I’ve never been drawn to photography because it makes me feel like an observer. And you are talking about photography like you are in it. You are in a moment, in a feeling… not just observing and documenting it. For me, being behind a camera makes me feel less connected because I’m not engaging. It’s more documenting. You don’t seem to come at photography that way.

SS: I see. It’s like it’s “you and stuff.”

If it’s a person – I’m thinking of some of the recent photographs I took in Burma – what I’m documenting is this amazing feeling that is associated with what was happening.

KF: And it sounds like you are documenting your feelings.

SS: Yeah… but what is theirs and what is mine? I don’t know where to draw the line.

KF: That seems like a plus of digital photography… that you can still be engaging and connecting while photographing at the same time.

SS: Yes, I love digital photography.

One aspect, print making, was certainly a more satisfying experience — being in the darkroom – than what it is now. In the darkroom, you are working toward something you will see in a while.

KF: That is magical. I’ve worked in a darkroom, and it is really cool to see an image appear, or re-appear, before your eyes.

SS: Yeah. But it’s like all the stuff you’re doing is not in real time. It’s about what it’s going to be. That is a rough way of working.

It’s really wonderful to be working in real time. It’s like coming back to the now. That’s what digital photography provides. You do something, and you can have an immediate response. You’re not a little bit in the dark.

So that’s wonderful, to be working directly on images. And then, digital cameras are much more flexible than film cameras ever were. It’s getting to the point with the technology that they’re becoming more sensitive. You can photograph in much wider conditions than you could with a film camera.

With a little extra work, you can use the digital to create what would’ve been really difficult with a film camera – panoramas or HDR where you can deal with much broader spectrums of light. You can shoot an interior with a window where there are clouds outside that are bright because they have sun on them and there are dark spots in the room. Trying to photograph that with film, you couldn’t do it.

Back in the olden days what I might do is take two photographs with the idea that somehow I would meld them together. I was able to do that with a lot of work. With digital, it’s not so much work. Actually, there are cameras that do that now all internally and immediately. What they’ll do is they’ll take several different exposures – say three different exposures – of a shot: one light, one medium and one dark, and then a program in the camera will go through it and pick the best exposures and blend them together into one shot.

This is what’s happening now with some of the smart phones. That’s why my wife can take a shot with her smart phone, and it looks great because it automatically has extracted the best exposures for just about everything in that shot.

KF: You talk about this very positively, but do you think it changes the realm of professional photography? Does the equipment give more people false confidence about their abilities?

SS: Well, if you want to be competitive, you could go wherever you want with that. But I look at the camera as a tool. It’s a remarkable tool that is able to take care of a lot of problems that would’ve been very difficult before.

I think nowadays with digital cameras, a lot of people have the attitude that anybody can take a great photograph. There’s another aspect to photography and art which has to do with heart. With feeling. With using your whole being. The camera is not going to do it all by itself.

KF: How do you stay motivated in the studio or to do work now when it comes up?

SS: When I was doing art festivals, I had a market place that was waiting for me, and I needed to be ready to sell things. I did everything I needed to do to have what I considered to be my basic inventory together. I don’t feel that pressure right now. And I’m okay with that.

If I have an order and somebody wants something, I’ll look forward to doing it because it’s satisfying and I’m working with quality. I’m always interested in doing quality and beautiful work. And I enjoy doing it. So, it’s always satisfying.

Lately I have been getting that need of mine to do quality stuff and keeping my eye sharp as far as making and working with Photoshop and programs that I use. I’ve been doing some commercial work which sort of verges on art work — I’m doing architectural photography.

I worked on a retrospective project for Jeff Gold, a very talented local architect, for his retirement. I’m always satisfied in producing what I consider to be quality work… in this case, they were beautiful.

Beyond that, a good way for me to do photography is to travel because that puts me in a novel place.

KF: Do you have any travel plans?

SS: I have vague travel plans for 2014… I’m thinking about Mexico. I’m easy. I don’t have to go far. I could go a couple hundred miles and be happy.

But going to novel places is good.

I’m still excited and look with relish at the prospect of being out whenever I am able to corral the time to do it. I’m ready to go and looking forward to it.

KF: Do you always have your camera with you?

SS: If I’m traveling, I will. My wife, Susan, and I went down to the Bay area recently for a high school reunion. We went to Ocean Beach; there’s a place we stay there that’s nice. I took my camera with me because I knew we might end up in the park. We went to the de Young, and I took it with me. So, I was taking shots in there… whatever I could see.

I don’t see it ever being old. The world is such a fascinating place, and there’s so much beauty to behold.